Origins & development.

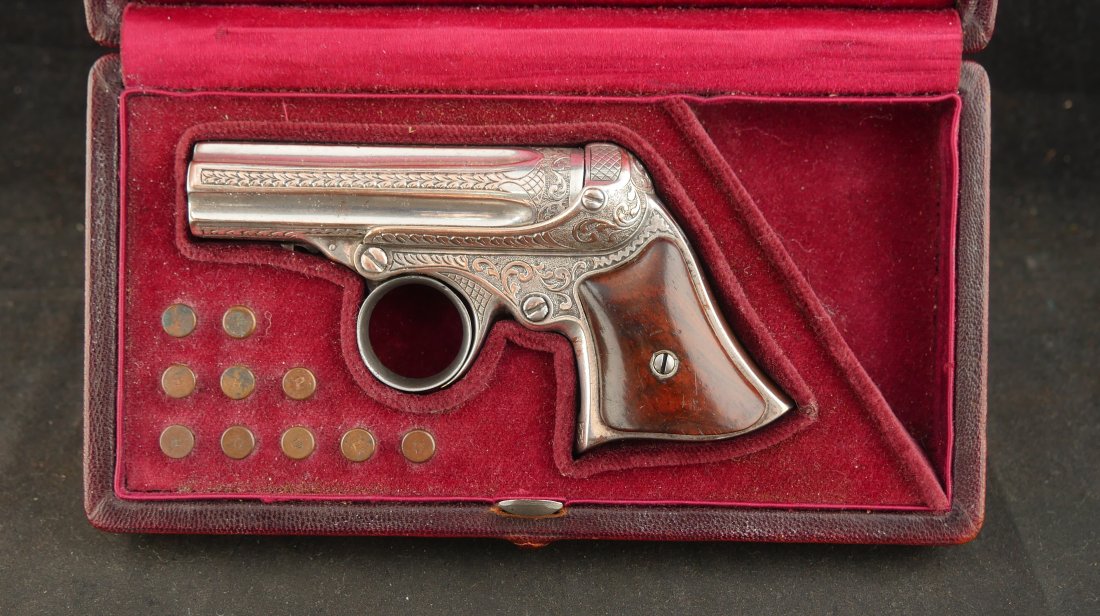

In the late 1850s and early 1860s, pocket defense shifted fast as the new .22 rimfire cartridge (introduced commercially in 1857) made tiny, reliable repeaters practical. Remington’s in-house inventor William H. Elliot patented a compact, hammerless “ring-trigger” mechanism (patents early 1860s) that rotated a small cluster of barrels and fired them in sequence. The goal was simple: give civilians a snag-free, multi-shot pistol that was safer in a pocket than a tiny single-action with an exposed hammer. Remington brought the design to market in the early 1860s, with production running primarily through that decade.

Design & how it worked.

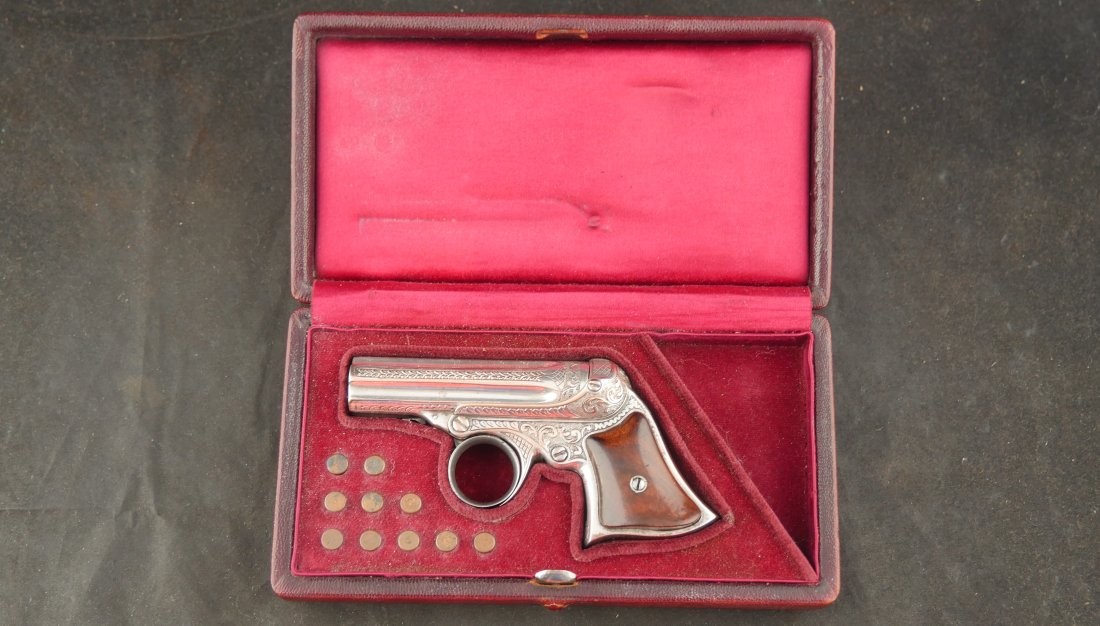

The .22 caliber Elliot is a true pepperbox: five fixed .22 rimfire barrels in a rotating cluster, all fired by an internal striker. The large oval trigger—Remington’s signature “ring”—both indexed the next chamber and released the shot with a steady pull. There’s no external hammer to catch on cloth, and the internal parts are well-shielded from lint and grit—important for a gun that lived in a pocket more than on a belt.

Why people bought them.

These were made for close-range personal protection in crowded American towns during and after the Civil War. Clerks, travelers, shopkeepers, gamblers—anyone who wanted five quick shots in a truly compact package—were the buyers. Compared to tiny single-shot muff pistols or two-shot derringers, the Elliot’s five-shot capacity was a selling point; compared to small revolvers, it was slimmer and smoother to draw from a pocket.

How it was carried & used.

Think waistcoat, trouser, or coat pocket, sometimes a small vest holster or a simple slip pouch. Period advertising emphasized quick access rather than formal holster carry. In use, it was a short-range, point-shooting gun: pull, present, and cycle the ring for rapid follow-up shots at a few yards. The .22 Short isn’t a powerhouse, but five fast shots in tight quarters was persuasive.

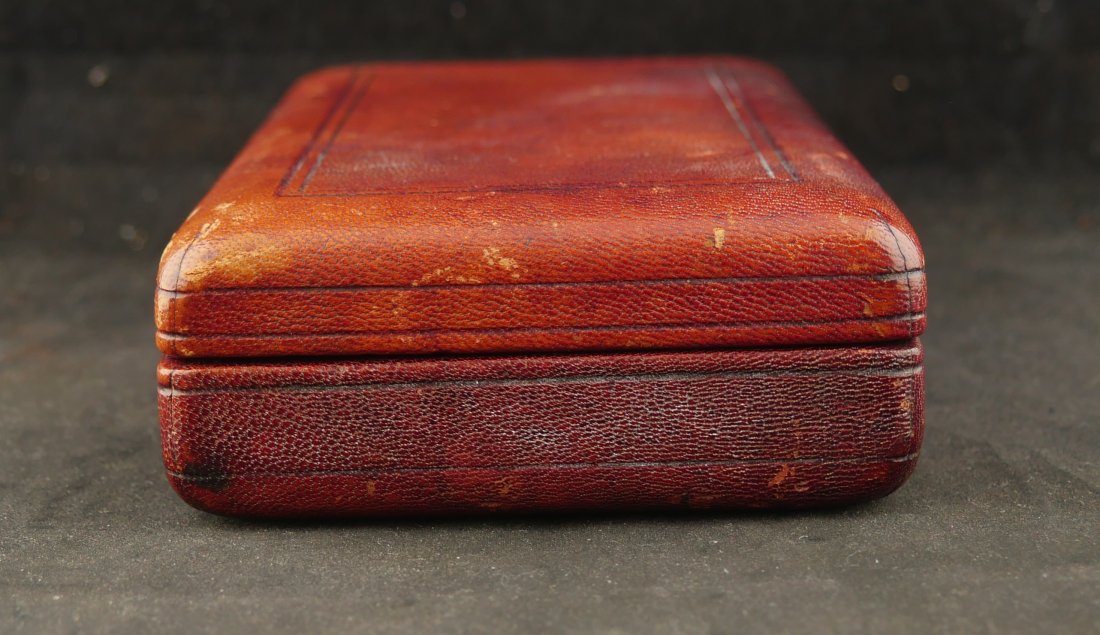

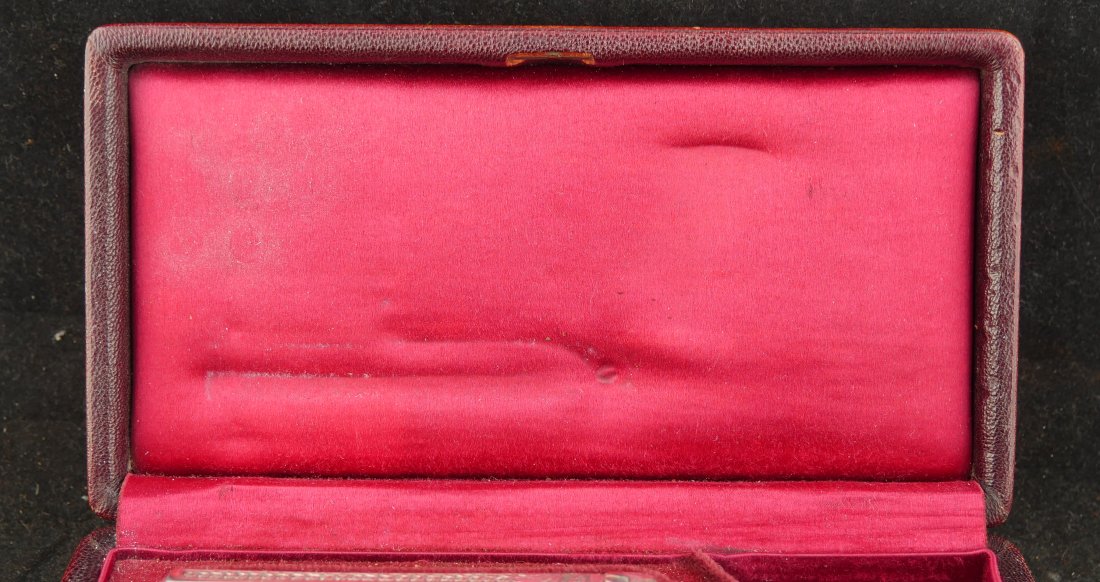

Finishes, engraving & scarcity.

Standard guns are typically plain with blued barrel clusters and plated frames. Engraved examples with a silver finish are genuinely hard to find. Silver-plated frames (and occasional full silver finishes) did exist, and Remington offered tasteful period scrollwork—often New York–style—on special-order pieces. But most Elliot’s were utilitarian pocket arms that saw daily carry, sweat, and pocket wear; elaborate finishes didn’t survive hard use, and far fewer were ordered that way to begin with. The fact that this gun is in such exceptional condition, with spectacular engraving and silver finish makes this a near impossible gun to find. Not many were ever manufactured with those features and even fewer have survived. This gun is truly an exceptional piece, one of the best you may ever find.

Reviews

There are no reviews yet.